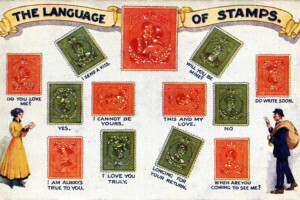

The Language of Stamps

By: John Deutch

Have you ever heard of the “language of stamps?” Sometimes a particular stamp will seem to “speak to me”… This usually occurs at a show or while I am reviewing the latest offers on eBay or Delcampe. But the “language of stamps” is something altogether different.

As some of you may know, besides Vatican City issues, I am also interested in French stamps and postal history. And among my French interests are the sower or semeuse stamps. Last year I was able to purchase a copy of THE SOWER, A COMMON LITTLE FRENCH STAMP by Ashley Lawrence, published by the France and Colonies Society of Great Britain. And it was a few brief paragraphs on page 224 in this book that brought the “language of stamps” to my attention. Lawrence writes that: “Readers of a certain age will recall the practice of endorsing the back of love letters with the secret message, SWALK…and for those in the know, this meant ‘sealed with a loving kiss.’ French lovers had similar means of passing secret messages to their paramours by using the “Language of Stamps”.

Those of us who collect postal history will sometimes come across a letter or a postcard with the stamp affixed in an unusual position or at an odd angle.

This is the “language of stamps”, something that began in England in the latter part of the 19th century. Picture postcards were then coming into their own, but the amount of space available for communicating one’s thoughts and feelings was limited. And there was no privacy, anyone could read whatever was written on the card. And so, the idea of an encrypted “special or hidden message” was very appealing. The position or angle of the stamp on a letter or postcard was supposed to relay a hidden or secret message to the recipient. This was the “language of stamps”. Lawrence writes that “if the stamp was tilted to the left, for example, the writer might be expressing ardent passion; if tilted to the right, he or she might be pleading for forgiveness.” And there were many other positions in which a stamp could be positioned, with each one conveying a different message. The “language of stamps” was so popular that in 1899 an Englishman by the name of George Bury published a little booklet that was titled CUPID’S CODE FOR THE TRANSMISSION OF SECRET MESSAGES BY MEANS OF THE LANGUAGE OF POSTAGE STAMPS.

From England the “language of stamps” spread to other countries. I have seen examples on eBay from Belgium, Germany, Switzerland, and the Netherlands, as well as those from France and Great Britain. In France there were a large number of sower postcards produced that clearly indicate the popularity of the “language of stamps”. Lawrence wryly observes that those who that those who manufactured these postcards doubtless assumed that French postmen were either illiterate or very discreet.